Why has my lawn gone patchy?

Author: Stefan Palm Date Posted: 9 January 2025

On a walk around my neighbourhood over the Christmas / New Year break, a fair percentage of the front lawns I walked by weren't looking great. It’s a common sight at this time of year, largely due to the summer conditions we experience here in South Australia.

When conditions get dry and hot, we inevitably have a rush of customers enquiring why their lawns are patchy or dying at a rapid rate. Sometimes, they bring core samples into our shop for us to look at, and other times, we go out on-site to inspect issues. Of course, there is a broad range of reasons why lawns can become patchy, including insect damage, disease, how they are used and maintained, etc; however, at this time of year, the number one cause comes back to moisture stress – in other words, the lawn isn’t able to draw enough water from the soil to remain green.

While this statement won’t come as a surprise to anyone reading this blog, moisture stress as the prevailing cause of patchy lawns is a factor that is largely overlooked when it comes to understanding why your lawn isn’t looking like you think it should. Let me explain.

Moisture stress is most often the result of two main issues:

1) Under watering:

Sometimes, you may think you are watering your lawn enough, but in actual fact, you aren’t. If you find that the timing of your lawn becoming patchy coincides with hot and dry weather, it’s worthwhile doing some checks on how you are watering. Ideally, during the summer months, Couch (sometimes called Bermuda grass) and kikuyu need around 25mm of water per week to remain lush and green. They will survive on less, but this is what would be required for optimal looks and performance. It’s worth checking that you are applying this amount of water evenly across the whole lawn surface each week.

The only way to know if you're watering enough is to physically check rather than to assume you are and the best method involves using Catch Cups. These are kind of like rain gauges that you place across your lawn. They come in a set of 12 and are used to measure how many mm of water falls on your lawn in a given amount of time. The idea is to set them up evenly across your lawn, water how you usually would (by sprinkler, irrigation system etc) and then look at how much water you collected. Check to see that you watered enough and that you applied the water evenly across the whole lawn. You might find that the dry patches receive less water than the green patches. When doing this exercise, it's common to find that you might not be watering enough or that your watering efforts are uneven. If this is the case, the best course of action is simply to adjust your watering practices accordingly.

2) The nature of the soil under the lawn:

After performing the above checks, you may be satisfied that you are watering enough but are still left with the reality that you have a patchy lawn, and that the soil under the lawn is dry. This is most often caused by soils that don't absorb or hold onto water. Water-repellent soils, often referred to as non-wetting soils, can wreak havoc on lawns, reducing their vitality and leaving patches of brown, unhealthy grass.

Where non-wetting soils are a problem, even if you were to go out and turn your sprinklers on to give your lawn a drink, the water would, in a lot of cases, runoff, and this is where a lot of people come unstuck. Because you have been watering, you automatically think the dead and dying patches in your lawn can't be a watering issue. The irony is that more water won't fix this issue either. You can test if you have non-wetting soil by watering your lawn as you usually would, then go out with a hand trowel and dig an inspection hole in the middle of a dead or dying patch. If the area is dry, then you've identified the problem. This is a lightbulb moment for a lot of people because you make the connection - how can the soil possibly be so dry right after I watered it? And the answer, of course, is that the soil has repelled the water.

Let’s delve into what non-wetting soil is, its causes, and how to address it to ensure your lawn remains lush and green.

What Is Non-Wetting Soil?

Non-wetting soil is a condition where the soil repels water instead of absorbing it. This results in water pooling on the surface or running off without penetrating the root zone. As a result, your lawn is unable to access the moisture it needs to thrive.

When water lands on non-wetting soil, it doesn't sink in evenly and either pools, runs off or evaporates rather than penetrating into the soil, so no matter how much you water it, the water doesn’t make it to where it’s needed, which means your lawn suffers from moisture stress. Not only that but since water is the carrier of nutrients to your lawn’s root zone, lawns growing on non-wetting soils are often nutrient-deficient, shallow-rooted and susceptible to disease.

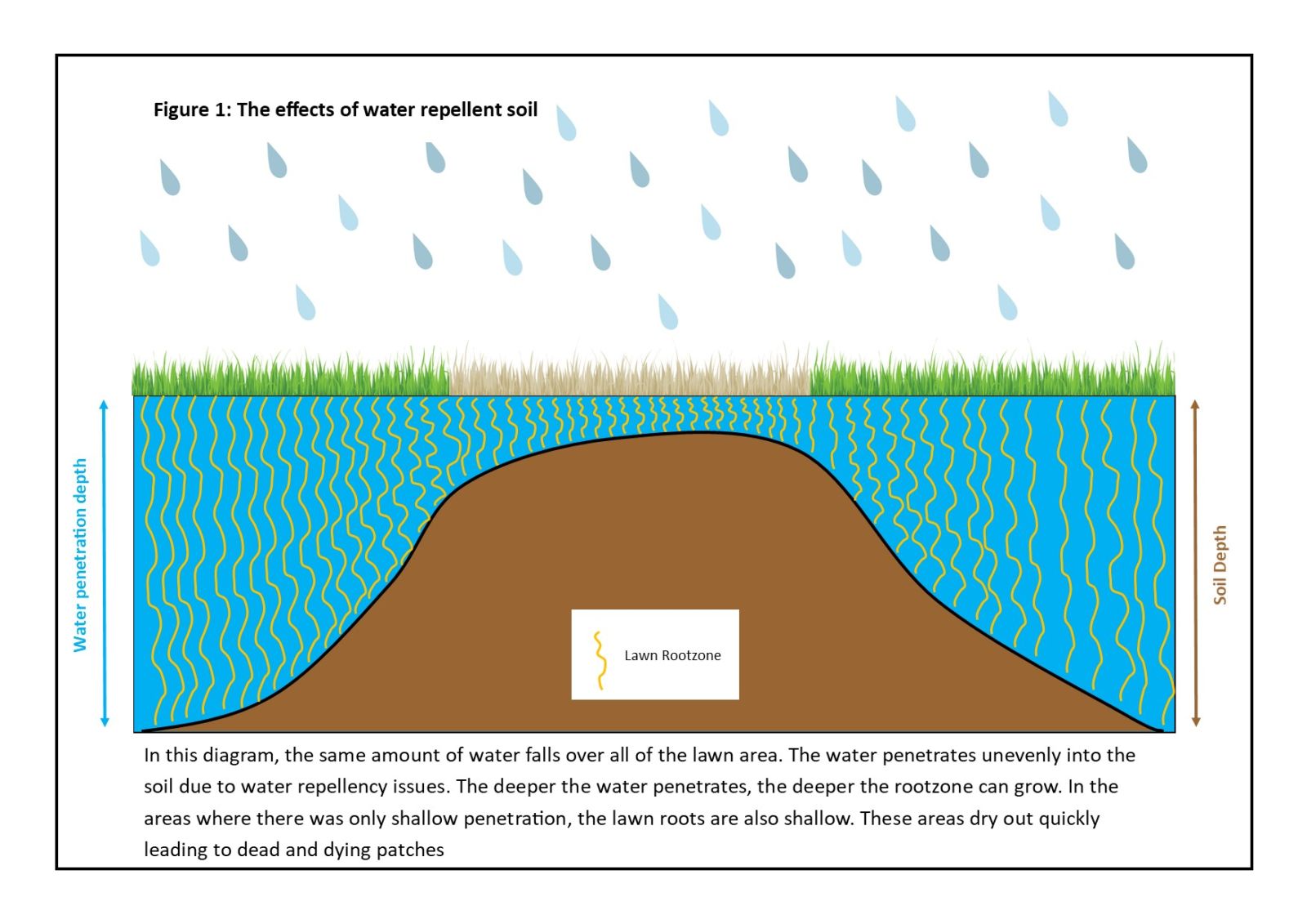

The table below helps to explain what happens when water doesn’t penetrate the soil evenly.

Causes of Non-Wetting Soil

The hydrophobic nature of soil is often caused by organic matter, such as decomposed plant material, coating the soil particles. This creates a waxy layer that prevents water from seeping through. Other contributing factors include:

- Dry Conditions: Prolonged dry spells, a hallmark of the Australian climate, can exacerbate the problem as organic coatings become more pronounced.

- Soil Compaction: Compacted soils can worsen water repellence, further hindering water infiltration.

- Excessive Thatch: A thick layer of dead grass and roots can act as a barrier, amplifying the hydrophobic effect.

Non-wetting soils are certainly more common during dry spells and during the warmer parts of the year. As is the case with many soil types in Adelaide, when they dry out to a point where there is very little moisture left in them, they are very hard to re-wet. Once they get super dry, they naturally repel water. It takes a lot of steady rain or irrigation to get them to take up moisture again.

Identifying water repellence.

In a domestic lawn situation, water repellence can be identified in 2 ways.

- The presence of a general patchiness in your lawn, with the soil being dry despite regular watering. This can be an all-over uniform dryness or random patchiness where you have brown patches amongst a green lawn.

- How long it takes for a droplet of water to penetrate the soil surface

Ideally, the soil under your lawn should be uniformly damp down to a depth of at least 50mm after irrigating. You can test if this by digging out a small 100mm core from a green area and another from a brown area in your lawn directly after watering. (If there are no green areas, just take a single sample from a dead or dying area). Firstly, do a visual check – If the green sample has moist soil and the brown sample is dry, you know you have a non-wetting soil problem since the whole area was doused with the same amount of water. A secondary check would be to apply a drop or two of water to the side of a dry soil sample. If it takes more than 5 seconds for the water to penetrate or the water simply rolls off like water on wax, then this would confirm you have a problem.

Statistically speaking, for every 100 core samples of turf we see, 45 of them have water-repellent soils. That means that around 45% of all dead or patchy lawns in South Australia are caused primarily by soils that won't absorb water!

How do you treat non-wetting soil?

The best way to treat non-wetting soils in a domestic lawn is with liquid wetting agents (not solid wetting agents). Liquid wetting agents do a couple of things – they help break down the waxy organic residues and they break the surface tension of the water, allowing it to penetrate into dry soils.

If you have non-wetting soil, you’ll have to apply a liquid wetting agent regularly during the summer months as a single application of wetting agent won't deliver any long-term results. A good rule of thumb is to reapply every six weeks during the warm months of the year for best results. The good news is that they are cheap to buy and available at most hardware stores. An interesting aside is that there are many types of wetting agents, some lasting longer than others and some having the ability to actually store water in the soil. You definitely get what you pay for – but that’s the topic for another blog!

My Recommendations:

- Wetting Agent: Apply a hose on a wetting agent such as Paul Munns Betta Wet every six weeks from November through to March every year in the following way:

- Apply wetting agents in the cool part of the day

- Irrigate your lawn prior to application with at least a 20-minute water for each watering zone

- Apply the wetting agent

- Water in well immediately after application with at least 25mm of water. That's about 30 minutes per zone or area with traditional popups or a sprinkler, or 1 hour per zone if you have gear drive sprinklers or mini rotors such as MP rotators or Rvan's

- Water Retention Agent: Once you have applied a wetting agent, apply a water retention agent such as SST Bi-Agra. Also available in a hose on pack, Bi-Agra is designed to hold water in the soil profile. A wetting agent enables water to get into the soil. A water retention agent ensures it stays there.

In my opinion, liquid wetting agents are the elixir of life for lawns and garden areas, whether you have non-wetting soil or not. They ensure that any rain or water penetrates evenly. They also reduce wastage of water because they make it possible for the water to penetrate quickly instead of evaporating or running off.

For what it’s worth, if you find yourself with a patchy lawn, the first thing I’d recommend you do is apply a wetting agent!

Comments (2)

Lawn - Dry Patches

By: Len Payne on 10 January 2025Thanks Stefan for that very helpful information and solutions. I am a 'sufferer' from 'dry patches' and will follow your great, detailed, advice. I am a regular customer at Paul Munns, so will need to come and see you again!!

Paul Munns Instant Lawn Response

Thanks for the feedback Len! Hopefully you see some improvement in your lawn, if not, give us a call on 8298 0555 so we can help you troubleshoot.

Lawn management

By: Nicole on 10 January 2025Your information on wetting agents is most helpful. However because my lawn was repelling moisture I have the added burden of patches of moss in my couch lawn. Can you advise me please.

Paul Munns Instant Lawn Response

Hi Nicole, thanks for the feedback! We have another blog post that goes into detail about moss removal, see here https://www.paulmunnsinstantlawn.com.au/blog/moss. If you have any questions, please email us on info@paulmunnsinstantlawn.com.au or call on 8298 0555.